Copyright � 2009 - 2018 Designed by: TailorMade Information Technology Solutions Ltd. All rights reserved. Site maintained voluntarily Markup Validation W3C XHTML 1.0 CSS Compliant |

A Short History of Woolpit[ Our Lady�s Well ] [ Museum ] Visitors to Woolpit often comment how attractive it is, and those of

us who live here would agree with them. As we return home along the A14

we are heartened to see the spire of our beautiful parish church

welcoming us long before we actually arrive in the village. Like almost every other settlement in Britain, Woolpit has a long and varied history, which stretches back for two thousand years. It is situated on the clay lands in the centre of High Suffolk. The parish now comprises the main village, the hamlets of Woolpit Green, Woolpit Heath and Borley Green and three outlying farms. The total area is 1877 acres. Perhaps the first mystery is the name. Some people have thought that it has something to do with wool, but the name first appeared in a document in 1005, long before the wool trade in Suffolk became prominent. Another possibility is that the village got its name because there was a wolf pit nearby. But the most likely explanation is that it came from the personal name of Ulfketel (which when translated means wolf (ulf) trap (ketel)). Ulfketel was a counsellor at the court of Aethelred the Unready (c.968 AD to 1016 AD). He was a famous warrior and is often referred to as the Earl of the Eastern Angles, so it would not be surprising to find a village named after him. In 1984 the Woolpit History Group began �field-walking� all the arable land in the parish, picking up shards of pottery. Three Romano-British sites and eight medieval sites were identified. All these sites were probably small farmsteads, and there is no evidence to support the former existence of any more substantial buildings. Some roman coins have also been found by workers on a building site, and this is further proof that the Romans were here. The first documentary evidence of the existence of Woolpit as a settlement is in 1005, when Ulfketel gave Wlfpet, along with five other manors to the Shrine of St Edmund at Beodricsworth, modern day Bury St. Edmunds, the year after the first battle of Thetford. The Abbot remained Lord of the manor of Woolpit until the Abbey was dissolved in 1538. In 1086 the Little Domesday Book recorded that there were 17 villeins, 3 bordars and 40 freeman in Woolpit. By multiplying those 60 men by a standard family number of 4.5, one can calculate that there were probably about 270 inhabitants in the manor of Woolpit in the late eleventh century. Nowadays the population is around 2000. In many ways Woolpit is a typical English settlement. The church is

in the centre, and a few steps away the old market place (currently

called Green Hill) is surrounded by brick-faced timber-framed houses and

shops dating back to the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Together with

part of the street leading to Bury St. Edmunds, this formed the

commercial centre of the village.

Most early medieval settlements were situated off the main road and Woolpit was no exception. The original road from Bury St. Edmunds to Ipswich can still be seen just over the northern parish boundary running alongside the A14. In the thirteenth century Woolpit was granted licences for a weekly market and two annual fairs. It is thought that this prompted the inhabitants to divert the main road through the village in order to encourage more business. Partly because of its central position in Suffolk, the village soon built up a good commercial reputation on account of its markets and fairs. It was also a popular place of pilgrimage throughout medieval times, because many people came to pray at the Shrine of Our Lady of Woolpit. This was a famous statue, which was almost certainly housed in the church in the area that is now the vestry. Throughout the Middle Ages bequests of land, money, jewellery, clothes and other items were left to Our Lady of Woolpit. The church therefore became rich, so much so that in the twelfth century the King appropriated the Abbey�s proportion of Woolpit�s tithes for himself. These tithes had previously been used to pay for the care of sick monks at the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, so the brothers felt very aggrieved about the King�s action. One monk, called Samson, decided to do something about it. Without permission from his Abbot, he and a companion dressed themselves as Scotsmen and set off to see the Pope in Rome, pretending to be pilgrims. They reached their destination and obtained a letter from the Holy Father restoring the tithes of Woolpit church to the Abbey. But on the return journey they were captured and searched. Samson managed to slip the precious letter inside a drinking cup, which he held above his head. It went undetected by their assailants, but Samson and his companion were left penniless and had to beg their way back to England. Eventually the tithes from Woolpit were reallocated to the sick monks and Samson later became one of the Abbey�s more famous abbots. Annual fairs were held around a village�s patronal festival (i.e. the

festival of the saint to whom the church was dedicated). In Woolpit�s

case this was at the beginning of September. There were two of them, the

Cow Fair and the Horse Fair. The Cow Fair seems to have been

In medieval times there were two gilds (or guilds) in Woolpit: the Gild of the Holy Trinity and the Gild of Our Blessed Lady. Wax, money and other items were left to these gilds. Unfortunately, the whereabouts of the two Gild-halls is unknown. In other villages local Gilds met in upper rooms of local inns, and it has been suggested that at least one of the Gilds could have met in the Belle Inn, which was situated in the centre of the village. Another idea is that the building which is now Addison�s store might have housed a Gild. Its unusual layout has certainly led some historians to speculate that this may have been the case. Each Gild would regularly collect a small amount of money from its members, which was pooled. The Gild�s money was then used to assist families who had fallen on hard times or help orphaned children to start an apprenticeship. But more importantly to the medieval mind, it would pay for the necessary prayers and the funeral when a breadwinner died. Afterwards, of course, the Gild would look after the widow and her children too. A well called Our Lady�s Well is situated north east of the church in a field called Palgrave�s Meadow. The earliest reference to the well is in the Manorial Extent of 1574 which in turn refers to an earlier survey in which a piece of land is �lying alongside the way which led to the spring called Our Lady�s well�. The water in the well had a reputation for healing sore eyes and when the water was analysed in the late 1970s it was found that it had a high sulphate content. Apparently it was more mineralised than other sources in the Bury St. Edmunds area, so there may be a crumb of truth in the legend that the water was a cure for sore eyes. The end of the Medieval Period is usually judged to be in the first half of the sixteenth century. Henry VIII was on the throne, and, after various disputes with the Church, began to dissolve the monasteries. St Edmund�s Abbey was dispersed in 1538 and all the lands with it. By the time Edward VI came to the throne in 1547 the pilgrim trade had ceased, but the village soon turned to a new occupation, that of brick-making. The first record of a brick kiln appears in the Manorial Extent of

1574 when two separate people In 1946 there was an attempt to re-open a pit. Unfortunately, late one day, a workman using a pickaxe hit a spring, and when the men returned the next morning the workings were flooded and unusable. So Woolpit no longer makes bricks, but the industrial tradition survives because there are light industrial units on some of the land which used to belong to the old brickworks. Finally, no history of the village, however short, would be complete without mentioning the legend of the two green children. Apparently, during the Middle Ages, a girl and a boy with green tinged skin were found in the fields near Woolpit by some villagers at harvest time. No one could understand their language and so they were taken to Sir Richard de Calne at Wikes Hall, near Bardwell, six miles away. They seemed to be hungry, but would eat nothing until they saw a servant carrying some green beans through the hall. When they were given the beans they devoured them instantly.

|

The ancient market place is triangular

in shape, and it was originally well supplied with inns. The old main

road snaked along the northern boundary, and another road went south

towards the Green along Whildrake Street (which is now called Green

Road).

The ancient market place is triangular

in shape, and it was originally well supplied with inns. The old main

road snaked along the northern boundary, and another road went south

towards the Green along Whildrake Street (which is now called Green

Road). discontinued some time in the seventeenth century, but the Horse Fair

persisted well into the nineteenth century, when it was abandoned

because it had become a magnet for thieves and pickpockets.

discontinued some time in the seventeenth century, but the Horse Fair

persisted well into the nineteenth century, when it was abandoned

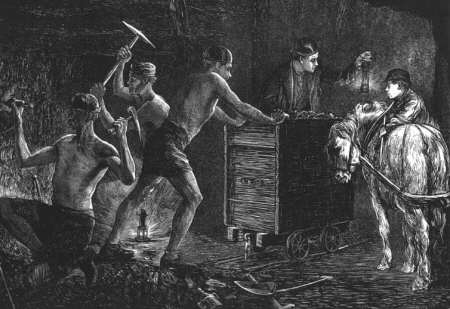

because it had become a magnet for thieves and pickpockets.  lived or farmed by �le bryckell�, and

clay-pits were mentioned too. By the eighteenth century the Brickworks

were an important part of the village and three working pits continued

to provide employment throughout the nineteenth century. They changed

hands several times, eventually being purchased by the London Brick

Company. In a modified form they continued to work until just before the

Second World War, when the government ordered that the kilns should not

be lit because of fears that enemy bombers would be able to see them

from the air.

lived or farmed by �le bryckell�, and

clay-pits were mentioned too. By the eighteenth century the Brickworks

were an important part of the village and three working pits continued

to provide employment throughout the nineteenth century. They changed

hands several times, eventually being purchased by the London Brick

Company. In a modified form they continued to work until just before the

Second World War, when the government ordered that the kilns should not

be lit because of fears that enemy bombers would be able to see them

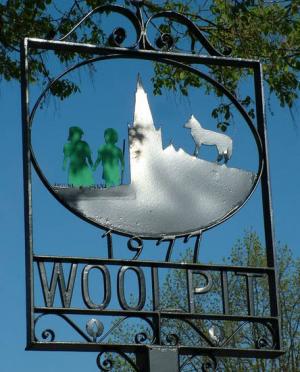

from the air.  The boy, the younger of the two, was always tired and lethargic and

eventually died, but the girl survived, and it is said that she married

a man from King�s Lynn. The legend was first written down by a monk

called Ralph of Coggeshall, who included it in his book The Chronicle of

England. At about the same time another monk called William of Newburgh,

who lived in a closed order in a monastery in Yorkshire, also recorded

the story. Reputedly, Ralph of Coggeshall travelled throughout East

Anglia in the late twelfth century, and tradition has it that he got the

tale from Sir Richard himself. William, on the other hand, probably

heard about the green children from travellers who called at his

monastery for shelter. The story may have grown in the telling. By the

time William heard it up in Yorkshire the children were definitely

green, whereas Ralph wrote that they were �tinged with green�. Of

course, it is only a legend but we do know that severe iron deficiency

due to lack of meat in the diet can produce anaemia, which in turn

causes tiredness and a greenish tinge to the skin. This is sometimes

called chlorosis, and it is possible that the two green children, if

they existed, had that condition.

The boy, the younger of the two, was always tired and lethargic and

eventually died, but the girl survived, and it is said that she married

a man from King�s Lynn. The legend was first written down by a monk

called Ralph of Coggeshall, who included it in his book The Chronicle of

England. At about the same time another monk called William of Newburgh,

who lived in a closed order in a monastery in Yorkshire, also recorded

the story. Reputedly, Ralph of Coggeshall travelled throughout East

Anglia in the late twelfth century, and tradition has it that he got the

tale from Sir Richard himself. William, on the other hand, probably

heard about the green children from travellers who called at his

monastery for shelter. The story may have grown in the telling. By the

time William heard it up in Yorkshire the children were definitely

green, whereas Ralph wrote that they were �tinged with green�. Of

course, it is only a legend but we do know that severe iron deficiency

due to lack of meat in the diet can produce anaemia, which in turn

causes tiredness and a greenish tinge to the skin. This is sometimes

called chlorosis, and it is possible that the two green children, if

they existed, had that condition.